My shopping cart

Your cart is currently empty.

Continue ShoppingIt is undoubtedly one of life’s delicious ironies that with the passage of time the once socially outcast become the venerable establishment. Today, after all, we have Sir Mick Jagger and Sir Paul McCartney. It’s probably true that we would have Sir Keith Richards if he were interested. He wouldn’t be the first knighted pirate.

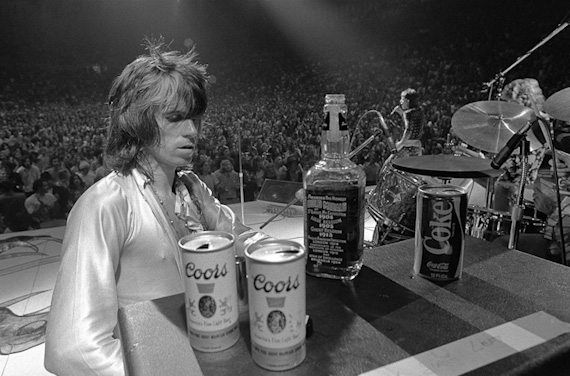

Keith Richards © Ethan Russell, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

As for the U.S, we deem celebrity royalty, pure and simple. Elvis is The King. I can’t imagine any President who wouldn’t have been delighted to shake his hand. Bruce Springsteen kept popping up like an heroic Knight throughout the inaugural festivities for Obama.

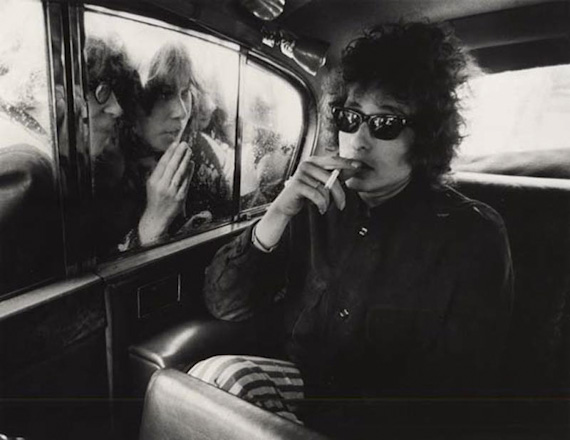

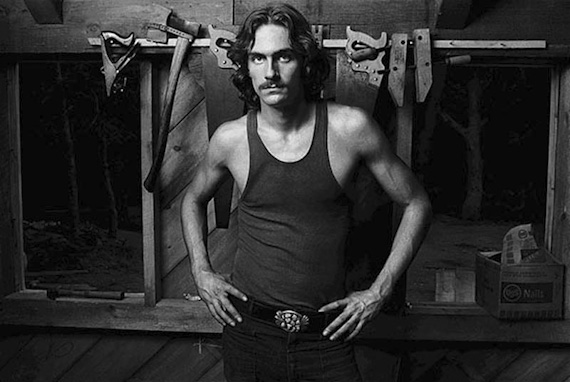

Bob Dylan © Barry Feinstein Estate, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

It’s just part of how rock and roll has become enshrined as it ages. (In 2009 “Who Shot Rock n Roll” was a major exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum of Art). The photography certainly deserves it. The history of rock n roll is astonishingly rich — visually, socially, acoustically - and essentially American. It is part of the legacy of the Fifties and the Sixties that the British were captivated by our music, consumed it, and then shipped it back to us, with bells on. Rock and roll became global.

A wall from the exhibition at Fahey/Klein.

The photography of rock and roll has ridden along on this road to enshrinement. In ways not worth elaborating upon here I think we all understand that the faces of rock, its style, its image have been inseparably connected with the music since its inception. So this recognition seems entirely as it should be. There is some extraordinary work that was created alongside the mundane, just like music. It is a “popular” art form.

David Fahey at the Fahey/Klein Gallery has assembled some of these photographs, and they are on exhibit until January 14th.

These are faces of artists who have changed the world. To see them in this environment is to experience them in a different way than to view them in books, on album covers, or on your computer screen. The prints - like their subjects - are analog, tactile, which is to say different from a collection of bits and bytes. To stand in front of them is to feel close to the artist in a palpable way. When a photograph is captured what in fact is happening is light bouncing off the subject is focused, captured, and stored on to the negative. At the time these photographs were taken - however many years ago - light bouncing off of Elvis or John Lennon or Bruce Springsteen was sealed in the negative that in turn created the print in front of you. It takes a little effort, but you can transport yourself to the moment of capture, as if linked.

Photography is a troublesome art. Some truly legendary photographers have dismissed it. And certainly an average practitioner, given luck and access, can produce results that are as impactful as the more skilled. But this should not diminish the value a photographer brings to their work. In this exhibition, Fahey has assembled the notable practitioners of the craft. I think anyone with a camera has the possibility of capturing history (think of the explosion of the Hindenburg) but the skilled artist photographer will capture moments of intimacy or excitement that would not be noticed or pass too quickly for the less-skilled. This is all in Fahey’s exhibition.

For me the opening evening included all these virtues along with some time to spend with my friends and peers.

In the exhibition there are three images of Elvis Presley. One of them (by Alfred Wertheimer) simply stopped me in my tracks the first time I saw it. More than The Beatles, The Rolling Stones or the Who, all of whom I was to work with, Elvis was my hero. When I was ten, I wanted to be him.

As an adult, many years later, working with a Southern singer songwriter, I happened to be in Tupelo Mississippi one dark night and came unexpectedly across the spotlit cabin where Elvis Presley was born. It was the simplest of structures, a single story two-room building without a foundation. In front, a simple covered porch. It was painted all white and at night with the spotlight on it, it glowed, like a shrine which it most certainly was.

In Wertheimer’s photograph Elvis is beautifully dressed in a suit, his hair is slick, combed, perfect. His eyes are droopily closed while his tongue protrudes almost daintily to touch that of the young woman in front of him. To me it was a startling picture: the intimacy and innocence of the man (of the time!) and the joy it somehow represented for a boy from the two-room shack in Tupelo. More “King of the World,” already, than Leonardo Caprio could ever hope to be.

Elvis Presely © Alfred Wertheimer, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

To this day there is something about the young Elvis, an intense, almost Greek-like beauty, that I think explains some of his universal and lasting appeal. Don’t ever underestimate the importance of beauty in art.

Elvis would become, as we all know, a virtual caricature, spawning imitators. It seems almost all of them choose to mimic the Elvis in his high-collared rhinestone-studded corpulent years and not this young God. Well, the latter would have been a lot more difficult to accomplish.

The same passage of time that transformed the socially outcast to the venerable establishment takes some of them with it. Of the photographers represented in the exhibition (see full list below) two - Jim Marshall, Barry Feinstein - passed away in the last year. It adds a sense of urgency to the work.

Once inside the room - it was jammed - I looked up to see two other photographers of my acquaintance, Norman Seef and Bob Seidemann.

Bob has taken some of my favorite photographs (two of which are in this exhibition). As opposed to a lot of the other photographers’ work - mine included - which benefited from the merits of journalism and good fortune of access - Bob’s often had an overt conceptualization that made his photographs less dependent of the moment than on the idea. His picture of the Grateful Dead standing like five horsemen of the apocalypse among the identical suburban houses of South San Francisco is as good a single image as I know to represent the wave of psychedelic change music would force into America in the early 1960s. The underexposure, the backlight, the silhouetted figures with the spot-lit faces (done with mirrors) combine to make the work successfully overcome the simultaneous virtue/impediment of photography which is that it’s “real.”

Grateful Dead © Bob Seidemann, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Norman Seef’s work popped into everyone’s focus - certainly mine - in the 1970s with his photograph of Carly Simon on the cover of “Playing Possum.” It is a wonderfully erotic photograph but without any of the manipulative intent and self-consciousness that we now see daily. This is one of the things that Norman was remarkably good at - the ability to loosen his subjects in the normally rigid environment of the photographer’s studio. I was a working photographer with my own studio at the same time Norman shot this image. I was going in the opposite direction, shooting large format film (4x5) on fixed tripods. The work - which could be wonderful when successful - was painstakingly slow and hardly any fun for anyone. I remember someone telling me how Norman was getting his photos. He had assistants holding the lights and the fans, so the entire experience was fluid, and it was an atmosphere more like improvisational theater than a photographer’s studio. You can feel it in the photograph.

Carly Simon © Norman Seeff, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

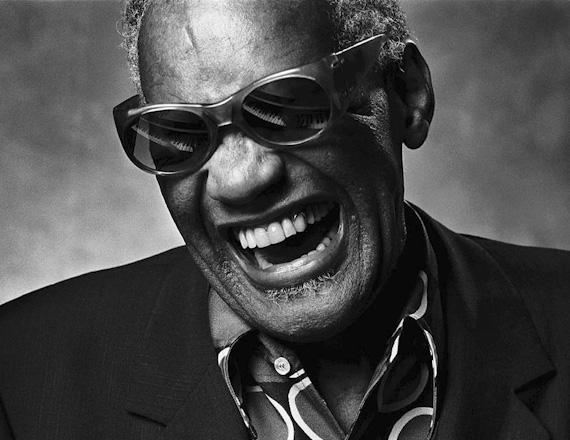

But it was not his picture of Carly that stood out for me in this exhibit, but rather his portrait of Ray Charles. Printed large it had for me the values I mentioned earlier. I felt I had a direct connection to the moment and the man. The quality of this particular image, wonderfully sharp and beautifully printed, welcomes you in.

Ray Charles © Norman Seeff, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

The artists photographed in the show include Elvis, The Beatles, Dylan, The Doors, The Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, The Clash, kd lang, James Brown, Joni Mitchell, and many others, too many for me to call out here.

Many as I said are famous photos, but some I had not seen before. Two I mention for personal reasons. The first is by Daniel Kramer, taken from the back of the stage, which shows Bob Dylan and Joan Baez silhouetted by the spotlights. It is a beautiful shot but not - in and of itself - revelatory. That angle and that image - the performer silhouetted by the spot - is common enough and in truth generally effective. But this photo is of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan and is representative of a particularly explosive time in music when my generation was being forged by it. Every person looking at this photograph may not have that association. It is - if the viewer but knew it - a more explosive moment than the Hindenburg.

Bob Dylan Joan Baez © Dan Kramer, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

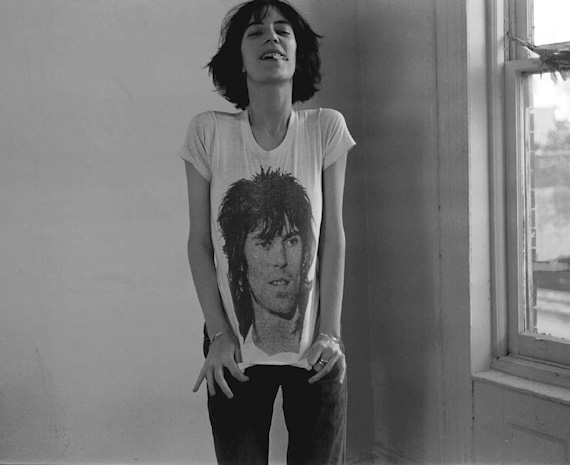

And the second was a photograph that came as a surprise to me. It is by Frank Stefanko and shows a delightfully young Patti Smith smiling (a rare enough moment) and holding the bottom of her t-shirt as if showing it off, which I feel certain she is. On it, is a printed black and white portrait of a young Keith Richards, circa 1970 something. Now they hang in the same exhibition together, and in this photo one can feel the sense of generation and family that rock and roll is now old enough to support.

Patti Smith © Frank Stefanko, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

We also see work from Henry Diltz who arguably is the principal chronicler of Crosby, Still Nash & friends, a lovely profile of k.d lang - like a Victorian silhouette - by Herb Ritts, a looming Jimi Hendrix by Gered Mankowitz whose early work with The Rolling Stones was the standard everyone else had to live up to, and beautiful David Bailey shot of Marianne Faithful very reminiscent of Bill Brandt’s photo of Francis Bacon. The list goes on.

James Taylor © Henry Diltz, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

“Faces of Rock II” is an exhibition you should catch. It not an exhibit of famous faces, it is an exhibit of important artists by skilled photographers. Together they made history.

The exhibition runs from December 1st - January 14th, 2012

Fahey/Klein Gallery

148 N. La Brea Ave.

Los Angeles, CA 90036

Ph: 323 934 2250

www.faheykleingallery.com

David Fahey by Ethan Russell