My shopping cart

Your cart is currently empty.

Continue ShoppingThis is the image I have in my mind: Herman Leonard, 65 years old, bowed and partly beaten, his marriage over, his 9 year old son and 14 year old daughter in tow, carrying a suitcase across a street in London’s Ladbroke Grove. If this were a Harry Potter movie the suitcase would be a talisman, with a slight animation to make it glow, dimly.

Inside the suitcase (to be stuffed under the bed in a temporary flat) are hundreds of 4x5 and 120 mm negatives, critical moments from the past of American Jazz.

Lost — and uncertain how to proceed — he attempts to interest galleries in his work. None are. Until finally in the summer of 1988 The Special Photographers Company in London decides to give him a chance. In one month 10,000 people attend.

I think I am drawn to this moment partly because I have observed over time: If you look into your future and can see it roll out with a certain predictability then you feel that life is good, but if you look out and only imagine uncertainty, then you are anxious. But, of course, in both cases you know the exactly the same thing. One wonders what Herman Leonard was thinking.

But outside of the human drama there are other elements at play, which have to do with Leonard’s extraordinary work, its value, and a warning about where we are today, photographically.

This blog is prompted by Herman Leonard’s last book JAZZ, which was sent to me by his son-in-law Stephen Elvis Smith. (Leonard passed away in the summer of last year at the age of 87). I had stopped in to visit with Leonard in his new home in Pasadena on my return from the Palm Springs Photo Festival in April of 2010. After years of living in New Orleans, Leonard was displaced by Hurricane Katrina. (Out comes that suitcase again.)

We traded prints. I signed two of my John Lennon images, and Herman gave me two of his. Although suffering from a terminal illness at the time, he was extraordinarily energetic, an interested and engaged look in his eye, and I privately envied his energy. It seemed a blessing.

It was an honor of course to meet him, and when he passed away it seemed an important light had moved on. But I had only met him that one time, and my memory of him diminished until leafing through his book that I received around Christmas.

His images are remarkable, and I was familiar with many. They are so technically achieved that at first you can be simply engaged with that: their clarity and, for lack of a better word, brilliance. It wasn’t until I had spent a little time leafing through his book that a second, even more important, quality leapt out at me, and that was their essential truth.

Dexter Gordon 1948

Like many I suppose I was at first most aware of his image of Dexter Gordon taken in 1948. It is a quintessential Herman Leonard photograph, combining the smoke curling from Gordon’s mouth, the smiling figure in the background, the angle, the close up intimacy and - in particular - Herman Leonard’s lighting.

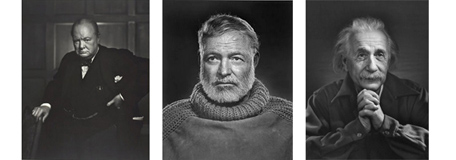

Yousuf Karsh Photos

There is a technical side to much of Herman Leonard’s work that bears mention. In the 1947 he apprenticed with another legend of photographic history Yousuf Karsh. Karsh’s trademark was the large-format studio portrait and in particular a lit studio portrait. It was a kind of lighting you could also see in many Hollywood portraits done from the time. The point is: Leonard learned Light. What he did - remarkably - was bring this into the jazz clubs. Speaking of this in an interview Leonard is somewhat dismissive of what he did, saying, essentially that he put his lights where the stage lighting was. And this may be true. But lighting is not one simple thing. It is the source light, of course, the primary instrument. But it - like music, like an intimate relationship - is the play between players. It is a) the light but also b) the angle of the light to the camera. And what Leonard clearly got was that there is nothing quite like 3/4 backlight.

I grew up being told when taking a photo to make certain the light was over my -I believe they said “left” for some reason - shoulder. There is almost nothing worse. When I was given this piece of technical advice in the 1950s it was the equivalent of the company - in this case Kodak - making the customer adjust to the limitations of their technology. Put it this way: using a little box camera with slow color film, more pictures are likely to come out if the sun is over your shoulder. Mind you, your subjects will be squinting and their faces gnarled up, but you will have your image.

In most of his photos of this era Leonard was using a large format camera as well, and lugging heavy lights to the gig. For some reason the amount of simple physical exertion expended and amount of technical expertise required to operate them - compared to today’s lights and cameras - caused me to think of a photograph I saw once of Sir Edmund Hillary’s (the first man to climb Everest ) climbing equipment. His shoes were made of leather! It is easy to overlook the obstacles our predecessors overcame and how much easier technology has made things over the years.

Whatever, Leonard found his technique and used it, to such an extent that some of his images might as well have been shot in a photographic studio.

These are wonderful images, but browsing through JAZZ one is rewarded with something even richer, that transcends technique.

The image that first triggered this response for me was a photo of Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker and The Metronome All Stars, New York 1949 (below) . What I saw here was simply true. I have photographed a lot of musicians in recording studios, and while this is a picture of Charlie Parker it is also an essential picture of musicians at work. I can feel them listening, no small feat.

Charlie “Bird” Parker and the Metronome All Stars. 1949.

Charlie “Bird” Parker and the Metronome All Stars. 1949.

Take for example, too, this utterly charming shot of Lester Young, poised, standing at the microphone:

Lester Young. New York, 1950

At this level (with this eye) the work seems focused on revelation equally as much as seeing, and it grows ever richer. Here we see moments of affection, really touching, that are released to us though they are far from “perfect” as photographs. This is a choice and to me it is the choice of an artist who understands his humanity and that of others.

Ella Fitzgerald and Dizzy Gillespie. New York, 1950.

Billie Holiday cooking a steak for her dog.

And despite an extraordinary claim by Edward Steichen that he couldn’t “hear the music” in Leonard’s photographs.... I feel it everywhere.....

Duke Ellington. Paris, 1959.

Duke Ellington

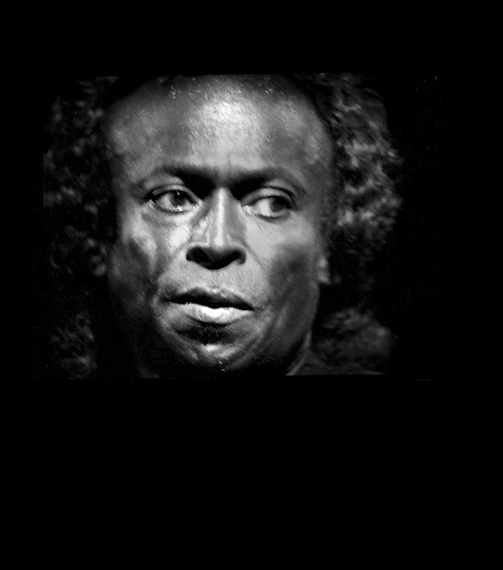

Miles Davis, Birdland, NYC, 1949

Not just in the playing, but also in the moments central to what they do, like the photograph of Sarah Vaughan about to on stage.

Sarah Vaughan. New York, 1950.

Or Louis Armstrong staring transfixed in a prototypical backstage moment.

Louis Armstrong. Paris, 1960.

All in all, JAZZ seems as intent on letting the reader into the world that Leonard knew as it does showcasing his work, and it seems to me that allows the reader several wonderful gifts: 1) to be where Leonard was allowed to go and 2) to be - because he was - a welcome guest, and then 3) be not just the beneficiary of his eye but of his spirit.

I think it is possible to deduce something from the fact that JAZZ is Herman Leonard’s last book, and he must have known that. He must have known this would be the collection that would uniquely represent him. In this light when I come to the last picture in the book, I am driven to consider his choice.

As a professional photographer there is always the process of selection. Of the many images shot and possible to release there are those that make the cut and those that don’t. Like any professional skill there are parameters that are straightforward. In carpentry, is the cut straight? In music, is it in tune? In photography, is it in focus, sharp? But there is a continuum, and other factors come into play. How is the lighting? Too harsh? I found as a young photographer that these rules were often sacrosanct. If I didn’t like the framing, out it went. But then over the years I started to notice the moments inside some of these frames.

The last picture in this book of Miles Davis is not a technically perfect photograph, especially if you’re Herman Leonard who - let’s remember - could pull a studio portrait from a live Jazz Session so crisp you could cut yourself on it. Instead it is on the edge, slightly soft. But what do I see? A man in reflection. A legendary man in reflection. He looks a little tired, like the road feels long. I don’t of course know what he is thinking, even looking at, but I know I am privy to a real moment with an extraordinary person. That feels like immense privilege, and part of the the unbelievable legacy that Herman Leonard leaves us.

Miles Davis. London, 1989.

And now my “warning.” The photography that Herman Leonard shot would most likely not be possible today. Managers would not permit access. Editors - especially of large circulation magazines - would not be interested in his work. The 6 minute photo op would be deemed sufficient. As readers, do we care? Herman Leonard’s pictures are not about excess or potential death. (Will Britney-Lindsay-Charlie Sheen survive?)

And there’s more, even if Leonard had managed to take the photographs, under most circumstances he would not own - or even have possession of - his work. This, commonly, is the lay of today’s photographic land. Remember the suitcase? It would have been empty. So, too, the museum walls. And if you like what you see? If you think it matters? It would be invisible.

Duke Ellington & Louis Armstrong, “Set of Paris Blues”, Paris, 1960.

You can buy JAZZ at Amazon and other online retailers.

You can see (and purchase) Herman Leonard’s work at:

AND AT

A GALLERY FOR FINE PHOTOGRAPHY

241 Chartres St., New Orleans, LA 70130

MORRISON HOTEL GALLERY

124 Prince St, NYC 10012

FAHEY KLINE GALLERY

148 North La Brea Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90036

JACKSON FINE ART

3115 East Shadowlawn Ave, Atlanta, GA 30305

EDELMAN GALLERY

300 W. Superior St., Chicago, IL 60654

ANDREW SMITH GALLERY

122 Grant Avenue, Santa Fe, NM 87501

All photographs © Herman Leonard unless otherwise noted.

Yousuf Karsh Photographs of Winston Churchill, Ernest Hemingway & Albert Einstein © Yousuf Karsh

This blog © Ethan Russell 2011.

ETHAN RUSSELL

web: www.ethanrussell.com

Blogs on Huffington Post: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ethan-russell/